CHAPTER 6

Home: Sweet—Home?

It will be nice to be home (I thought apprehensively), although the living conditions at 13432 Moenart would not have the comfort and privacy I had grown accustomed to as an eighteen-year-old bachelor. Roaming the “world” for the past eight months, I enjoyed an uncommon freedom from the watchful eyes of caring and diligent Catholic parents. All my life (at least from third grade on), I felt an uneasy yearning to escape the fetters of parental supervision and the dogmatic practices of Catholicism.

I unconsciously appreciated the cloistered protection that both afforded, but I felt restricted with a lack of individual freedom. The parochial school discipline, exacted by the nuns who guided my questionable educational progress, carried with it moral and academic suspicions. And my own parents reinforced the common code of corporal punishment for “crimes” venial and mortal. Both adhered strictly to an “old-testament” admonition: “Spare the rod, and risk spoiling the child!”

The psychology of that era, and those preceding it, must have been to “burn down the barn to make sure you got rid of all the rats.” The “God of mercy” was conveniently lost sight of during trying times, like the “Inquisition” and child-rearing. And where exactly did Christian philosophy (dogma) begin adulterating Jesus’s practice of extolling highest virtue to children (Jesus’s request of those field hands not to tear out the weeds before the wheat grew to maturity surely rings true here).

I suppose there was some benefit, somewhere, in my parents’ adherence to strict Church doctrine. But a child under its absolute enforcement would be hard-pressed to commit his own life to its rigidity and merciless extraction. I can’t forget being slapped (on an almost daily basis) across the face or on back of the head by parents and teachers alike—for simple acts of omission or using language and tones of voice that didn’t sit right with the offended adult.

It was not uncommon for me to be “bludgeoned” at school by a teacher who would afterward send for one of my younger siblings and give him or her a note to give to my parents. When my dad got home from work, he would remorsefully yet without hesitation administer another ration of what came to be standard procedure in a typical day in the life of a certain young Catholic boy. But I also can recall that on many of those occasions, the supervising adults would grimace slightly and then apply what seemed the mandatory response to their religious obligation. I believe they thought it was their duty to do what they did. (I didn’t then, but I now feel sorry for them.)

When—and if—I ever have kids, I hope the “psychology of the day” will have instituted a more soothing means for reaching children, other than by “corporal punishment.” It doesn’t work! Especially if adults want to gain the genuine respect and appreciation of children and young adults that they proclaim to enlist—and not “spoil the child”!

My dad should have had sainthood bestowed on him, for all his self-sacrifice. The virtue he displayed while providing for his family of ten was truly commendable. (But nevertheless, because of the manner with which we related to each other, it wasn’t so much respect but rather fear that got my divided attention.) He worked from early adulthood on the assembly line at the Plymouth/Chrysler Plant on Mount Elliot Road, about two and half miles from where we lived. He didn’t always have a car to get to work, but he never missed a day of work. When he was ill, there were no “sick leave” and vacation days to recuperate. The health and welfare of his family were too important to miss work for any reason. I remember him walking the distance on repeated occasions in blistering, snowy conditions because the car wasn’t functional and no bus routes were available to him.

He always made sure that there was always enough good food available for Mom to prepare at mealtimes. At those harder times when we were “on Welfare,” none of us kids wanted to go with him to pick up the groceries with “food stamps” (for fear of being seen by someone we knew). I also remember seeing him waiting until the entire family finished a tasty, nutritious dinner before he sat down and finished what was left—even if they were merely the scraps from off the plates we had left behind.

He could hardly afford it, but he made sure that his children had a good Catholic school education. For some reason, he didn’t want to send us to public school, even though it was free! Transfiguration was a prosperous Polish Catholic elementary school six blocks east of Moenart, on Syracuse Street. I think the church gave us a discount, since I recall Dad doing things for “them” in his “spare time.”

White School was the public elementary school—right down the street from us on Moenart, on the south side of Luce, not even a quarter of a mile away from our house. (I sometimes wished I was going there. Then I wouldn’t be forced to learn the Polish language, which most of the kids felt was meaningless, inferior, and difficult— especially for poor students who weren’t even Polish.)

One of the many things that we—kids (at least to my personal recollection)— didn’t fully appreciate at the time was the amount of effort Dad (Mom as well) spent on seemingly trivial things concerning us rather than focusing on his own personal needs. I can still picture me and my siblings kneeling down in the living room and

saying aloud our evening prayers before we could go to sleep. Dad wanted to make sure we all knew the words and said them with conviction. From what I remember as a considerably long time, we said them together.

Eventually, he had the notion that we might learn them in Polish as well as English. The attempt was futile, since we could barely say them in English, and that was only if we said them a hundred miles per hour, remembering the rhythm.

We always started off our litany with eyes closed, in solemn reverence to the “sign of the cross.”

“In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost,” as we uniformly performed the action with the right hand, from head to heart, to left shoulder, to right shoulder.

Immediately after, we would recite the Lord’s Prayer (Our Father, who art in heaven . . .), followed by the “Hail Mary” (Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee . . .).

In Polish, it would read, “W imie Ojca I Syna I Ducha Swietego.” The Lord’s Prayer followed, “Ojcze nasz, którys jest w Niebie, swiec sie Imie Twoje . . .” And the Hail Mary, “Zdrowas Mario, laskis pelna . . .”!

Since I was the oldest, the initiating of this common ritual naturally fell upon me. Everything proceeded well, over the months that we participated in the nightly regimen. But if you can imagine the monotony that set in after weeks and weeks of this religious banter, you might wonder if something (anything) might have occurred that would have broken the monotonous stream of rhythmic cadence.

One evening, at a moment when the proceedings were to begin, and we were settling into our kneeling positions, I somehow preemptively—and apparently unconsciously—began the “sign of the cross” with a somewhat emphatic recitation of the numbers: 1, 2, 3 . . . But before I could finish “3,” Tom and Marilyn had busted out laughing, and I became deliriously conscious of the fact that I might soon be the recipient of a hard slap across the back of my head or face.

As it “miraculously” turned out, while my neck and shoulders were cowering to the right and away from where I presumed the blow would be coming, the eyes of my twisting head caught sight of what appeared to be a slight, momentary chuckle projected from the contorted lips of both my parents. It didn’t mean I wasn’t still going to be nailed, but it did offer at least a temporary reprieve from any retribution for an obviously sacrilegious, desecrating impropriety of scandalous proportion.

After a few moments for all to regain the proper composure to continue, the prayers were concluded, and we all retired to what would be a “good night’s sleep”— all things considered. To what could I attribute such a heartfelt impulse of “forgiveness”? The gesture was hardly used in conjunction with disciplining children or students. So I must have unconsciously chalked it up to a previously unknown fact that, occasionally, “God has a sense of humor.”

As the days, weeks, and months passed, the ritual stopped. And we were permitted to say the evening prayers in the semiprivacy of our own bedrooms, of which there were three. Dad and Mom had one; Marilyn and Joan shared one; and Tom and I shared the other. When Bobby, Mike, Carole, and Jimbo came along, the comfort level was considerably strained with some inconvenient adaptations.

Dad could be observed as a model of virtue, mostly by others, but sometimes even by me. I would hear relatives make mention of times—in the not-so-recent history—when Dad’s generosity secured some relative’s successful venture. It ultimately provided him and his family a well-established means of financial security.

Uncle Zig and Auntie Annie lived a comfortable life, largely due to Dad’s generous loan at a time when he was the only one working. He carried the burden of assisting much of his extended family. Those recipients of his initial generosity never forgot his unselfish gestures and always made sure our family of ten was never without the “necessities” of life. And on special occasions, even a luxury or two!

His virtue extended in ways I could hardly understand, especially at a time when our family was on “Welfare.” Somehow it was evident that my eight-year-old mentality didn’t quite grasp how honesty was the best policy. When opportunities arose and a quick gain could be made if only I would deny the “honesty factor,” I would hardly abide with a policy to which my dad was a strict adherent.

One cold winter evening, my dad was putting on his boots, which five minutes earlier he had taken off after shoveling the snow from off the walkway in front of our house. He had planned to spend the rest of his evening relaxing before going to bed. I thought it odd because there seemed no legitimate reason for such action. Plus, he had to get up earlier than usual the following morning, to walk to work since the family car was at Uncle Zig’s Garage being repaired.

He had been out earlier that afternoon, walking half a mile through the snow to Bazaar’s Confectionary. He usually purchased his pack of cigarettes there, on Sundays, since nearer neighborhood stores were closed.

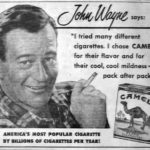

(In 1953, it had not yet been established that cigarette smoking could be hazardous to health. In fact, it was encouraged to promote good healthy living.  As an eight-year-old, I tried it once. But when told by friends to inhale, I almost gagged in pain and never tried it again. And at seventeen cents a pack, even my dad could afford it. I can remember that he sometimes sent me, an eight-year-old, during the week to Bloom grocery—the first street east of Moenart—with a quarter to buy him a pack of Camels.

As an eight-year-old, I tried it once. But when told by friends to inhale, I almost gagged in pain and never tried it again. And at seventeen cents a pack, even my dad could afford it. I can remember that he sometimes sent me, an eight-year-old, during the week to Bloom grocery—the first street east of Moenart—with a quarter to buy him a pack of Camels.  I would sprint from our backyard, through the alley, and be back in less than three minutes, with the Camels and eight cents change. Once, in a while, he’d let me keep a penny to buy a thimble of pumpkin seeds.)

I would sprint from our backyard, through the alley, and be back in less than three minutes, with the Camels and eight cents change. Once, in a while, he’d let me keep a penny to buy a thimble of pumpkin seeds.)

It was later that evening, while counting the money he had in his pants pocket, he noticed a discrepancy in the amount that was there. When he initially left home and traversed the snowy terrain between our house and “Bazaar’s,” he had a $10 bill. But when he perused the contents of his pocket afterward, he counted $19.82, nine

teen dollars and eighty-two cents. (Bazaar’s charged one penny more than the other stores for cigs.)

The store attendant gave Dad $10 too much change. To my way of thinking, Dad just made a $10 profit on his cigarette deal. So I was more than a little annoyed when Mom told me he was on his way back to the store to return the extra money. I couldn’t believe it! Who else would do that? I knew I wouldn’t. If I had an extra ten bucks, I’d be in heaven. At least temporarily! Obviously, I had not yet attained any apprehension of the “metaphysical” dimension of life. By the way, the attendant gave Dad a free pack of cigarettes for his trouble.

(I guess his “honesty” paid off when the true facts about smoking came out a few years later. Dad quit “cold turkey” and never had a problem with his lungs or his breathing before his death in 2004.)

Next: Chapter 7 – New Revelations!