To those who would, and could, be Great, I have prepared a Series of essays that are meant to awaken these supreme athletes to the subtle facts as to why they are presently deficient in achieving their collective Goal, and suggest a means to enhance each one’s prospect for ultimate Fruition.

GIANCARLO STANTON WILL BE GREAT WHEN HE MAKES THESE ADJUSTMENTS!

Inspired Thought stimulates the action of the human body to either modest or grand achievement via practical utilization of Universal Laws governing their perfect mechanical application to the mental/physical apparatus.

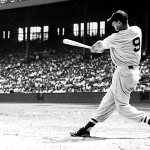

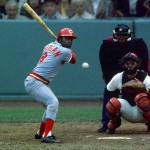

What’s wrong with the picture above? The average baseball fan would normally conclude that the body of the person on the right could not possibly respond to a pitched ball in the same manner as the person (player) on the left. But the contradiction merely emphasizes that a magnificent physique does not assure a baseball batter of the good effect he would desire unless his mechanical advantage corresponds to how powerfully built he is.

The following is a short passage from my new Book, If I knew Then What I Know Now :

“If the darkest hour always precedes the dawning of a new light, then when its brilliance comes to full effulgence, does it not seem reasonable to presume that “one’s finest hour should prefigure some form of impending gloom? Could greatness be sustained within the grasp of hubris? Greatness is a humanly exaggerated or a spiritually magnified sense of being. To be extolled with greatness, one must step up above one’s peers, beyond the casualness of conformity, into the altitude of ‘Uniqueness,’ wherein the atmosphere of Soul the inspiration of life a lesser man cannot inhale.”

In my previous essay series entitled The Best!, beginning on June 27, 2015, I again featured Giancarlo as my first example of a player whose nearly perfect mechanics would qualify him as one of the best of the Best. As I described his greatest mechanical advantage then, it was his ability to maximize his strength and fluid “hip-action” to produce a centrifugal-force that accommodated his inherent body-hand-eye coordination. Although his slight stride and open-stance were his only observable flaws (read the early essay to find out why), he was still capable of maintaining fluid horizontal and parallel hips to negotiate an unfettered swing.

(Batters of a now generation have come to speculate that a hitter gets a better view of the pitched ball if his body is “frontally” positioned so his eyes could see the ball more directly. The concept is impractical not only because while striding toward the plate he turns his body sideways to the pitched ball anyway, but he also presents himself with an inaccurate visual acuity to the moving projectile coming from less than a straight angle.)

Last season, Giancarlo finally figured out that the movement from the Open-Stance must have diminished his visual capacity, so he changed to a closed-stance, and reaped the rewards that his more stable head and eyes and new confidence afforded — 59 Home Runs and National League MVP. Unfortunately, his obsession with his new and effective stance must have turned the wheels of his brain to think that “If a slightly closed-stance was good, would it not be even better to exaggerate the ‘closed-ness’ a little more”?

The consequence of trying to accommodate a well functioning body with the hubristic aggrandizement of the mortal brain has presented Giancarlo with the debacle he is faced with at the present time. His extremely closed-stance does not allow for his hips to freely and fluidly rotate through his previously prodigious hitting zones

.His hips now stop half-way through their range

.His hips now stop half-way through their range of motion

of motion , forcing his shoulders and upper body to disassemble his powerful “vertical-axis,”

, forcing his shoulders and upper body to disassemble his powerful “vertical-axis,” and have his arms work independently from their main power-source – his body. On inside fastballs, he can’t bring his body through the contact point. Then, on breaking balls away, he unwittingly finds his hips opening too quickly when the pitch starts inside. And, as the pitch is moving away, he is in no position to use his “spent-body,” and flails away with his arms.

and have his arms work independently from their main power-source – his body. On inside fastballs, he can’t bring his body through the contact point. Then, on breaking balls away, he unwittingly finds his hips opening too quickly when the pitch starts inside. And, as the pitch is moving away, he is in no position to use his “spent-body,” and flails away with his arms.

Apparently he and his teammates are presuming his dreaded slump is over. But his Home Runs against Houston on Wednesday, May 2 were the result of his natural athletic prowess and Keuchel’s mistakes. Even though his hips only proceeded to the half-way point, he somehow waited long enough to stretch his powerful arms in the direction of that outside pitch and mustered a “not so propitious drive” into the short Right Field stands – Hoorah!

His second Home Run was off a breaking pitch inside and low, where his prematurely-spent opened hips were in the right position for his lunging upper body to facilitate the downward action of his powerful arms and hands to flick a “screaming-mimi” into lower section of Houston’s short Left-Field pavilion. He also had a double on a subsequent at-bat, and a 4 RBI night. It was a well-acclaimed performance based solely on his natural athletic prowess and uncommon strength. Let’s see if his next games are as fortuitous as Wednesday’s.

If however, he would like to feel confident that he is more than a physical phenomenon who can sporadically excite the fans with heroic feats of monumental proportion, and consistently refrain from becoming the tragedian embodiment of epic disillusionment, he must first “change the way he looks at things (baseballs) so he can clearly see the things at which he is looking. Then, he must apply the “Perfect Principle of Perfect Practice to his otherwise mechanical advantage of hitting a baseball.

When Adrian Beltre was with the Dodgers, his stance was opened, and he was erratic in batting effectiveness. Later, he changed to a closed stance, and eventually became the potential Hall of Famer he is today, after making adjustments to a closed-stance that is not so extreme as Giancarlo’s.

In watching Giancarlo take batting practice for a television commercial, he was in a moderately closed or even stance, and took no stride at all, and successively hit scorching ascending line-drives that went over the fence. He should use that same approach in games, except address the pitcher in a lower stance, for a lower center of gravity which will assure quickest possible reaction, like Mark McGwire and Barry Bonds did.

Coming Soon: Yu Darvish, then Aaron Judge.

His Stance is a little-thing that facilitates the Big-Thing as you will notice below — His zig-zag Stride toward the plate, and away. Watch the horizontal and vertical movement of head and eyes.

His Stance is a little-thing that facilitates the Big-Thing as you will notice below — His zig-zag Stride toward the plate, and away. Watch the horizontal and vertical movement of head and eyes.

In the picture to the left, his hands and stance are lower, providing a lower center of gravity and faster reaction time. But his zig-zag stride to and away from the plate not only presents visual distortion, jeopardizes his front foot plant to possible injury, but makes him vulnerable to hard breaking pitches moving away from him. The inside fastball (in view) is right in his “Wheel-House,” and a pitch all pitchers should avoid throwing to him.

In the picture to the left, his hands and stance are lower, providing a lower center of gravity and faster reaction time. But his zig-zag stride to and away from the plate not only presents visual distortion, jeopardizes his front foot plant to possible injury, but makes him vulnerable to hard breaking pitches moving away from him. The inside fastball (in view) is right in his “Wheel-House,” and a pitch all pitchers should avoid throwing to him.

Once he gets his front foot down and planted, he has the best and most mechanically sound swing in Baseball. Since he is already the strongest man in the Game, he must ask himself, “What can allow me to be most consistent in swinging to make solid contact with the baseball? Why do I need to stride? I don’t need extra forward, linear movement to gain momentum of force to propel the ball out of the park! The rotary action of my hips and shoulders (after my front foot is planted) is certainly powerful enough to make sufficient contact of my bat to the ball — especially while I’m seeing the ball with optimal acuity, by not moving my head and eyes.”

Once he gets his front foot down and planted, he has the best and most mechanically sound swing in Baseball. Since he is already the strongest man in the Game, he must ask himself, “What can allow me to be most consistent in swinging to make solid contact with the baseball? Why do I need to stride? I don’t need extra forward, linear movement to gain momentum of force to propel the ball out of the park! The rotary action of my hips and shoulders (after my front foot is planted) is certainly powerful enough to make sufficient contact of my bat to the ball — especially while I’m seeing the ball with optimal acuity, by not moving my head and eyes.”