Reduce Margins for Error

In all walks of Life, from a professional baseball player to a rock musician, from parenting to managing a business, a respectable accomplishment can be ultimately attained only after the process of trial and error has been satisfactorily consummated with a high-quality finished product. Until that has happened, one can assume that, in all of these life-challenges, the margins for error that seem to be natural retardants to proper development have not been reduced sufficiently to produce a genuinely finished product.

A legitimate “prospect” for becoming a proficient baseball player eventually must master all the intricate details for hitting (and throwing) a baseball effectively. He will never make it “Big” until his concept of “hitting” (or throwing) complies with the principle that is the most probable means for facilitating optimal proficiency. The principle of Batting (and Throwing) is the scientific application of body-mechanics, based on the understanding of factors that influence the effect that the bat has on a “pitched” ball (and the effect that body, arm, hand, and fingers have on the ball thrown).

As most ardent sports enthusiasts already know “hitting a baseball effectively is the single-most difficult act to perform in all of Sports.” Why? No other individual sport-skill encompasses the variety of challenging variables that a batter has to “put in order” to be a proficient “hitter.”

Along with physical attributes of strength, flexibility, quickness, balance, and coordination, as well as the mental accoutrements of courage, confidence, determination, and fortitude, the proficient bats-man must ascribe to a technique of proper mechanics that facilitates the most probable means for making solid contact with a pitched baseball in what is considered an acceptable proportion of his “at-bats.”

In professional baseball, batting averages ranging from .300 to .399 are considered high quality hitting, with an annotation of “superlative” attached to those that exceed the .350 mark or flaunt with the barrier of .400. But most ball-players fall far short of consistent .300 – hitting prowess.

Natural athletic ability does not seem preponderant in determining batting proficiency at the highest level. All batters seem to have their own individualistic style for expressing their highest hopes of masterful bats-man-ship.

There does not seem to be a standard approach (“techne”) that would be considered fundamental to the purpose of maximum efficiency in hitting a baseball. Some players stand tall; others crouch low. Some hold their hands and bat high, while others hold them low.

Players address the “plate” in either an open, closed, or even stance. Most batters take a stride, either away, toward the plate, or toward the ball (or practice a “high leg-kick”). They tend to push off the back foot while straightening the back leg as the weight of the body is either trying to stay back or lunge forward.

Some hitters think that maintaining even shoulders while swinging will facilitate a “level swing” for effective line-drive contact. Others perceive that by swinging downward onto the front part of the ball, the bat will effect a “back-spin” on the ball that will allow it to carry through the air longer and farther. Some batters cock their wrists back for extra power, and consider themselves “wrist-hitters” when they exhibit fast hands while rolling the bat through the ball quickly. Some batters maintain loose hands and wrists while they are swinging so that relaxed muscles will propel the bat more quickly through the strike zone. And still others (like Babe Ruth) squeeze the bat tightly, from start to finish, and rely on the speed and strength of the turning body to impact the bat onto the ball with a force to counteract the speed and power of the pitch.

From the contents of the preceding paragraph, is it possible to delineate the characteristics that might lead to the creation of what could be considered the quintessential professional bats-man? The answer is NO!

The pronounced characteristics mentioned in the foregoing illustration enumerate the “margins of error” that exacerbate the promising intentions of all prominent prospects for batting excellence:

- A “Tall” stance

creates a large and easy strike zone for the pitcher, as well as proposes a line of vision for the batter’s eyes that transcends countless horizontal planes in following the flight of the ball to the plate

creates a large and easy strike zone for the pitcher, as well as proposes a line of vision for the batter’s eyes that transcends countless horizontal planes in following the flight of the ball to the plate . The eyes that will see the pitched ball most clearly are those that come as closely as possible to the level of the ball in flight

. The eyes that will see the pitched ball most clearly are those that come as closely as possible to the level of the ball in flight . Also, the taller the stance, the higher the center-of-gravity, the weaker and slower the body’s action, the lesser the prospect for a most effective swing.

. Also, the taller the stance, the higher the center-of-gravity, the weaker and slower the body’s action, the lesser the prospect for a most effective swing. - When the batter’s hands and bat are held high

, he unwittingly has created for himself a high center-of-gravity, which for all practical purposes diminishes the leverage by which the maximum speed of the body can be facilitated in turning the hips and shoulders. A low stance, with bat and hands at the level of highest strike, facilitate the fastest body action(Joe Morgan – above).

, he unwittingly has created for himself a high center-of-gravity, which for all practical purposes diminishes the leverage by which the maximum speed of the body can be facilitated in turning the hips and shoulders. A low stance, with bat and hands at the level of highest strike, facilitate the fastest body action(Joe Morgan – above). - Of the three stances, the open-stance is the most deleterious to proficient batting

because it tends to force the batter to stride toward the plate and therefore makes him vulnerable to hard inside pitches. Because the stride itself is moving the body, along with head and eyes, the movement toward the plate compounds the distortion aspect of the moving pitch.

because it tends to force the batter to stride toward the plate and therefore makes him vulnerable to hard inside pitches. Because the stride itself is moving the body, along with head and eyes, the movement toward the plate compounds the distortion aspect of the moving pitch. - Any stride at all is a major contributor to batting dysfunction. It is useless expenditure of energy whose purported function of initiating momentum is overrated.

It becomes counterproductive to optimal visual acuity, as the head and eyes move also. If the hips move forward with the stride, the integrity of the swing itself is compromised by the dislocation of the body’s “vertical axis.” Maximum power is impossible to generate while the vertical axis is not constant. The “high-leg-kick”

It becomes counterproductive to optimal visual acuity, as the head and eyes move also. If the hips move forward with the stride, the integrity of the swing itself is compromised by the dislocation of the body’s “vertical axis.” Maximum power is impossible to generate while the vertical axis is not constant. The “high-leg-kick” is a detriment to effective hitting because the batter never knows exactly when to put that “plant-foot” down, especially on off-speed pitches.

is a detriment to effective hitting because the batter never knows exactly when to put that “plant-foot” down, especially on off-speed pitches. - Pushing off the back foot while striding gives the false impression of producing power to initiate the turn of the hips during the swing.

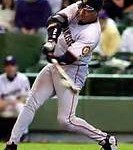

In fact, the push-off impels the back leg to continue to straighten, the effect from which restricts the turning of the hips to their maximum. The optimum hip and shoulder actions occur only when the back bent knee maintains its same bent position as it rotates through the entire hip rotation. (ala Barry Bonds)

In fact, the push-off impels the back leg to continue to straighten, the effect from which restricts the turning of the hips to their maximum. The optimum hip and shoulder actions occur only when the back bent knee maintains its same bent position as it rotates through the entire hip rotation. (ala Barry Bonds)

- The stride and the push-off may force the body to “lunge forward” to try to counteract the “magnetic pull” of the in-coming fastball. However, off-speed pitches will force the batter to hesitate by gliding forward on a bent front knee

, affording no balance, nor power to swing because of the disintegration of the vertical axis, and premature turning of the hips. The hips should always be ready to turn quickly in a “turnstile” fashion, both sides in opposite directions, on the same horizontal plane, with the vertical axis intact.

, affording no balance, nor power to swing because of the disintegration of the vertical axis, and premature turning of the hips. The hips should always be ready to turn quickly in a “turnstile” fashion, both sides in opposite directions, on the same horizontal plane, with the vertical axis intact.

- Parallel shoulders, while striving for a level swing, is a misconception of the ideal of good intent. If the shoulders stay level throughout the swing, at the presumed contact point the top hand will be forced to roll over the ball because the hips and shoulders have reached the limits for forward movement, and the arms will extend to keep the momentum. However, if the front shoulder is in a “shrugged” up-position, and the back shoulder lowered with a driving back elbow

, the bat and ball will meet as the palm of the top-hand is facing upward

, the bat and ball will meet as the palm of the top-hand is facing upward . The horizontal rotation of the hips and bent back knee preclude any possibility of an upper-cut swing, as long as the front upper arm is in contact with the chest.

. The horizontal rotation of the hips and bent back knee preclude any possibility of an upper-cut swing, as long as the front upper arm is in contact with the chest. - Swinging downward onto a downward moving pitched-ball is more often counterproductive to efficient bats-man-ship than it is productive. The pitcher is on a mound almost a foot above the plane that the batter is on

. Every pitch is moving downward into the strike zone. If a batter with good eyesight and good coordination strikes downward onto the pitched ball, his athletic ability will probably enact solid contact a high percentage of times. Solid contact in those instances will result in balls hit on the ground. (Albert Pujols and Gary Sheffield are examples of such a hitter.) The “best of hitters” is not merely one who makes solid contact with the ball. But rather, he is a batter whose body mechanics facilitate the action of the swinging bat to contact and continue through the ball at an angle that provides for a straight (non-hooking or slicing) and ascending “line-drive.” The “Art” of hitting a baseball could certainly be defined in the context of describing the ideal hitter– “He is one whose bat most consistently contacts and drives through the ball in a manner that facilitates a straight and ascending “line-drive.”

. Every pitch is moving downward into the strike zone. If a batter with good eyesight and good coordination strikes downward onto the pitched ball, his athletic ability will probably enact solid contact a high percentage of times. Solid contact in those instances will result in balls hit on the ground. (Albert Pujols and Gary Sheffield are examples of such a hitter.) The “best of hitters” is not merely one who makes solid contact with the ball. But rather, he is a batter whose body mechanics facilitate the action of the swinging bat to contact and continue through the ball at an angle that provides for a straight (non-hooking or slicing) and ascending “line-drive.” The “Art” of hitting a baseball could certainly be defined in the context of describing the ideal hitter– “He is one whose bat most consistently contacts and drives through the ball in a manner that facilitates a straight and ascending “line-drive.”

(To hit the ball in any other manner would be to miss-hit it.)

(To hit the ball in any other manner would be to miss-hit it.) - “Cocked-wrists” may deceive the batter into thinking he will have a stronger swing because of the extra action he expects to have at the “contact–point.” The extra action is counterproductive because the timing mechanism to produce a synergistic display is unreliable at best. Also, neither “cocked forward” nor “cocked backward” is the strongest position for the wrists to be in. Straight and stiff is the strong position of hands and wrists for swinging a bat, as it is for a Karate punch. What would happen if you punched a “bag” with wrist and hand cocked in either the forward of backward position? Right! Remember, the power of the swing comes from the body. But if the hands are not in their strongest position on the bat at contact, the ball will impact the bat more effectively than the bat will impact the ball; and the pitcher will win that battle.

- Relaxed hands to begin and tight hands to finish through the “contact point” is a good rule to follow. With continued “loose-hands” through the “contact,” the ball controls the bat. But if a tight grip occurs at “contact,” the ball will sound and feel like a golf- ball. The bat should be gripped with the strongest part of the hand, not in the fingers.

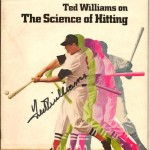

- In the preceding photo you will notice not only that Ted Williams’ is gripping the bat with the strong part of the hands, but also, as his custom was, he “choked-up” on the bat, not holding it on or below the knob. Most hitters, especially those who strike out a lot, usually have their hands on or below the “knob” of the bat. They generally think that that extra “leverage” will allow them to hit the ball farther. But those great hitters who seldom struck out, and are also known for their propensity to hit many Home-Runs, were much more scientific in their approaches to hitting:

Joe Morgan,

Joe Morgan,  Ted Williams,

Ted Williams,  Barry Bonds,

Barry Bonds, Don Mattingly, to mention a few. They understood that it was not so much the length of the bat, but rather the control and power that the body gave the bat that propelled the ball the distances necessary to display the ultimate swing. When a batter (whose hands are below the knob) just misses “his pitch” by fouling it straight back (especially when the pitch is slightly away – where he can extend his arms), he doesn’t understand that the extra length adds weight to the extended shoulders, and the extended bat dips slightly under where he thought he was swinging. On that same kind of pitch, the batter (Barry, Joe, Ted, or Donny) would more often make solid contact because they were better able to compensate the extension of their shoulders and arms – less weight.

Don Mattingly, to mention a few. They understood that it was not so much the length of the bat, but rather the control and power that the body gave the bat that propelled the ball the distances necessary to display the ultimate swing. When a batter (whose hands are below the knob) just misses “his pitch” by fouling it straight back (especially when the pitch is slightly away – where he can extend his arms), he doesn’t understand that the extra length adds weight to the extended shoulders, and the extended bat dips slightly under where he thought he was swinging. On that same kind of pitch, the batter (Barry, Joe, Ted, or Donny) would more often make solid contact because they were better able to compensate the extension of their shoulders and arms – less weight. - Most people might surmise that the surface muscles of the upper portion of the arm and shoulder juncture come into play when getting the front arm ready to enact its movement in swinging a baseball bat. The “deltoid” muscle, as it is known, contracts to lift the upper arm away from the body as it prepares for the swing. But if the deltoid muscle alone is thought to be the stabilizing mechanism to begin the arm involvement of the swing, the strength necessary for the number of intricate functions is drastically reduced. Therefore, I assert that a driving force of parallel shoulders, to bring the arms and bat to the ball, is not what is essential. A more correct elaboration of the action of the upper body would be to insist that all the muscles of the “shoulder-girdle” (including the trapezius, supra-spinatus, etc.) contract to lift the entire front shoulder, while stabilizing the arm socket. This provides not only a stable reference point from which to begin the twist-turn of the swing, but is also the initiating agent for flattening the bat as it is to begin its approach to the ball. With these large muscles in complete control of the upper arm, the facilitation of proper arm-action for the swing is now set in order. The arm-socket is locked into position. Now, the turning thrust of the entire body provides a powerful centrifugal force which disperses its energy through the connection of a tightly bound shoulder joint, through the extending front arm, to the viselike grip of the stiff wrist-hand-fingers. In conjunction with the action of the front side of the upper-body, is the coordinated action of the backside. When the front shoulder “shrugs” upwardly, it automatically creates an opposite reaction for the back shoulder and corresponding arm, elbow, and “top” hand. The back shoulder pulls downward, bringing the back bent-elbow to a low vertical position, and changing the position of the top hand to one above and even with the back elbow, with the bat flattening in its approach to the ball

. As the body reaches the point of full expression of power (the legs, hips, and shoulders having brought the arms and bat into the “range of decision”) the batter has to decide whether to complete the mission (attack the ball), or quickly abort (hold up). If the pitch is a strike, then a full commitment is in order, and the front forearm extends through a locking elbow (whose upper arm is just releasing from the chest, to extend away from the body), assisted by way of the driving force of the extending back arm. If the shoulders continue in the “follow-through” in a manner which allows for the front shoulder to end up in back, and vice versa, and the bat goes through the ball with the top-hand in a “palm-up” position, then the batter can assume an optimum effectiveness in the swing. If the pitch is not a strike, all the momentum built up by the powerfully turning body would have to come to an abrupt halt. Fortunately, if the batter’s preliminary front shoulder preparation was correctly applied, the large muscles of the “shrug” will supply adequate force to stop the arms from committing the bat too far over the plate, and prevent an inadvertent strike-call. It would be virtually impossible to stop such a powerful force of momentum with just the strength of arms alone, or the wrists and hands.

. As the body reaches the point of full expression of power (the legs, hips, and shoulders having brought the arms and bat into the “range of decision”) the batter has to decide whether to complete the mission (attack the ball), or quickly abort (hold up). If the pitch is a strike, then a full commitment is in order, and the front forearm extends through a locking elbow (whose upper arm is just releasing from the chest, to extend away from the body), assisted by way of the driving force of the extending back arm. If the shoulders continue in the “follow-through” in a manner which allows for the front shoulder to end up in back, and vice versa, and the bat goes through the ball with the top-hand in a “palm-up” position, then the batter can assume an optimum effectiveness in the swing. If the pitch is not a strike, all the momentum built up by the powerfully turning body would have to come to an abrupt halt. Fortunately, if the batter’s preliminary front shoulder preparation was correctly applied, the large muscles of the “shrug” will supply adequate force to stop the arms from committing the bat too far over the plate, and prevent an inadvertent strike-call. It would be virtually impossible to stop such a powerful force of momentum with just the strength of arms alone, or the wrists and hands.  (You can always tell a batter who does not understand the value of the “Shrug” by the frequency with which he cannot hold up on a “close-pitch.”)The “Shrug” is definitely the least exposed secret in the “Science of Hitting.” Most players would deny its validity on the mistaken grounds of two illegitimate hypotheses. First, that the shoulders are supposed to remain parallel throughout the swing to assure a “level-swing.” Secondly, that an upward tilt of the front shoulder would automatically include a high risk of the batter’s “popping-up.” The truth to both of those matters is that the “shrug” is beneficial to maintaining a level swing as well as in preventing a high frequency of “pop-ups.” Parallel shoulders, throughout the swing, prevent the top hand from completing the process of palmation, thus forcing a premature rolling of the wrists over the descending ball, in a majority of swings (e.g. Eric Karros). While the shrug helps to level the bat to the plane of the ball, the turning body and extending arms supply the power and direct guidance along the same line as the descending ball. Also, more pop-ups occur when a bat is swung on a downward angle at a downward moving ball. That is unless the ball is hit squarely, which, of course, would result in a ground ball, most other times!Most of the great Power-Hitters of Today and Yesteryears, especially Home-Run hitters, used the “Shrug” in their applications to the swinging of the baseball bat. All you have to do is watch films of the great hitters like Willie(s) Mays and McCovey, Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Babe Ruth, Roger Maris, Mark McGwire, Barry Bonds, Albert Pujols, Ken Griffey Jr., Sammy Sosa, and Ted Williams, just to name a few. And if you look closely at the initial move of the upper body, as the swing begins, you will notice the tilt of the shoulders, either consciously or unconsciously, created by the “Rodney Dangerfield” of the Perfect-Baseball-Swing—“The Shrug.”

(You can always tell a batter who does not understand the value of the “Shrug” by the frequency with which he cannot hold up on a “close-pitch.”)The “Shrug” is definitely the least exposed secret in the “Science of Hitting.” Most players would deny its validity on the mistaken grounds of two illegitimate hypotheses. First, that the shoulders are supposed to remain parallel throughout the swing to assure a “level-swing.” Secondly, that an upward tilt of the front shoulder would automatically include a high risk of the batter’s “popping-up.” The truth to both of those matters is that the “shrug” is beneficial to maintaining a level swing as well as in preventing a high frequency of “pop-ups.” Parallel shoulders, throughout the swing, prevent the top hand from completing the process of palmation, thus forcing a premature rolling of the wrists over the descending ball, in a majority of swings (e.g. Eric Karros). While the shrug helps to level the bat to the plane of the ball, the turning body and extending arms supply the power and direct guidance along the same line as the descending ball. Also, more pop-ups occur when a bat is swung on a downward angle at a downward moving ball. That is unless the ball is hit squarely, which, of course, would result in a ground ball, most other times!Most of the great Power-Hitters of Today and Yesteryears, especially Home-Run hitters, used the “Shrug” in their applications to the swinging of the baseball bat. All you have to do is watch films of the great hitters like Willie(s) Mays and McCovey, Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Babe Ruth, Roger Maris, Mark McGwire, Barry Bonds, Albert Pujols, Ken Griffey Jr., Sammy Sosa, and Ted Williams, just to name a few. And if you look closely at the initial move of the upper body, as the swing begins, you will notice the tilt of the shoulders, either consciously or unconsciously, created by the “Rodney Dangerfield” of the Perfect-Baseball-Swing—“The Shrug.”

The “Premier Batting Principle” is based on the perfect application and integration of all the preceding components!

* The proper body-mechanics for throwing (Pitching) is described in another essay, COMING SOON!

)might at first exude a confidence that he normally has when “dad” is softly lobbing the ball into that part of the strike zone

)might at first exude a confidence that he normally has when “dad” is softly lobbing the ball into that part of the strike zone  where his natural body mechanics allows his arms and hands to synergize the coordinates of his swinging bat to contact the ball with remarkable proficiency and redirect the pitched ball on the ground, or in the air, in the opposite direction.

where his natural body mechanics allows his arms and hands to synergize the coordinates of his swinging bat to contact the ball with remarkable proficiency and redirect the pitched ball on the ground, or in the air, in the opposite direction.

. Every person who picks up a bat, to hit a baseball, wants to hit a “Home-Run” (over the fence), or at least a solidly contacted ascending line-drive that could split the outfielders and allow his speed to garner a double, triple, or an “inside-the-parker.”

. Every person who picks up a bat, to hit a baseball, wants to hit a “Home-Run” (over the fence), or at least a solidly contacted ascending line-drive that could split the outfielders and allow his speed to garner a double, triple, or an “inside-the-parker.” , but their reality usually has them settling for merely making contact with the pitched ball, and hoping that a grounder through the infield will get them a base-hit. Their instincts tell them that only “big-guys” can hit the ball over the fence for Home-Runs.

, but their reality usually has them settling for merely making contact with the pitched ball, and hoping that a grounder through the infield will get them a base-hit. Their instincts tell them that only “big-guys” can hit the ball over the fence for Home-Runs.  . And, what better way for a youngster to find the right form or technique than to copy the batting stance and swing of his favorite Major League Player?

. And, what better way for a youngster to find the right form or technique than to copy the batting stance and swing of his favorite Major League Player? , Stan Musial, Babe Ruth

, Stan Musial, Babe Ruth

, Yogi Berra, Joe DiMaggio, Lou Gerrig, Al Kaline, Dick McCaullif, Norm Cash, Rocky Collivito, Willy Mays, Hank Aaron, Duke Snider, and others.

, Yogi Berra, Joe DiMaggio, Lou Gerrig, Al Kaline, Dick McCaullif, Norm Cash, Rocky Collivito, Willy Mays, Hank Aaron, Duke Snider, and others. constituted a precise manner for which to hit a baseball most efficiently was revolutionary for his time. But, in the aftermath of his great and successful career, he attained many ardent followers, But few were able to understand and duplicate his relevant and practical theories, and their applications.

constituted a precise manner for which to hit a baseball most efficiently was revolutionary for his time. But, in the aftermath of his great and successful career, he attained many ardent followers, But few were able to understand and duplicate his relevant and practical theories, and their applications. The “Premier Pitching Principle” leaves most modern batters at a loss for productive bats-man-ship. But what the “modern batsmen” fail to realize is that there is a Principle for Batting that would supersede the predominance that the “modern pitcher” seems to have acquired.

The “Premier Pitching Principle” leaves most modern batters at a loss for productive bats-man-ship. But what the “modern batsmen” fail to realize is that there is a Principle for Batting that would supersede the predominance that the “modern pitcher” seems to have acquired.

Then why would someone (like myself) have the audacity to declare that “Batting-Efficiency is a Simple Process”?

Then why would someone (like myself) have the audacity to declare that “Batting-Efficiency is a Simple Process”?

Whoever it is that is perpetuating the imperfect batting-mechanics of the distant past should start thinking “outside the box,” like whoever it is/was that was the vanguard for the innovative thinking that produced the likes of Masahiro Tanaka, Takahiro Norimoto, and others who have become the new standard for Pitching Excellence. (Maybe some fortunate Japanese pitching aspirant wandered into the instructional Pitching Camp of Resident Arizona Pitching Guru, Dick Mills, and learned a few things about Pitching Conditioning and Mechanics!)

Whoever it is that is perpetuating the imperfect batting-mechanics of the distant past should start thinking “outside the box,” like whoever it is/was that was the vanguard for the innovative thinking that produced the likes of Masahiro Tanaka, Takahiro Norimoto, and others who have become the new standard for Pitching Excellence. (Maybe some fortunate Japanese pitching aspirant wandered into the instructional Pitching Camp of Resident Arizona Pitching Guru, Dick Mills, and learned a few things about Pitching Conditioning and Mechanics!)